The Middle East suffers, at best, from an ambivalent reputation. Simultaneously very old and very new, incredibly fecund and extremely barren, the Arabian Peninsula is home to both some of the most elegant and some of the most vulgar cultural phenomena of today. It is the former this article will celebrate, and the author hopes recent events will not disproportionately mar judgments of the general with the particular. In the aftermath of senseless acts of violence by a non-representative, repellent and miniscule – though turbulent – minority, it is perhaps ever more pressing to seek that still small voice of calm; to wonder at the beautiful rather than be paralyzed by the ugly. If rage breeds war, then beauty is calming. From the architects of Ancient Egypt to those of our times, buildings have served as sanctuaries to man, as places of teaching, living and learning. The word ‘museum’, come to us via the identical Latin word designating a ‘library’ or ‘study’ is itself originally derived from the Ancient Greek ‘Mouseion’, meaning ‘shrine of the Muses’. They are, then, intended as places of inspiration, and Jean Nouvel’s designs befit this original purpose remarkably.

“Architecture has to be a gift.” — Jean Nouvel in Reflections (2016)

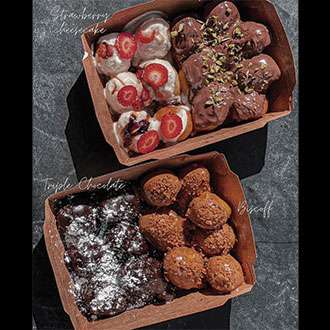

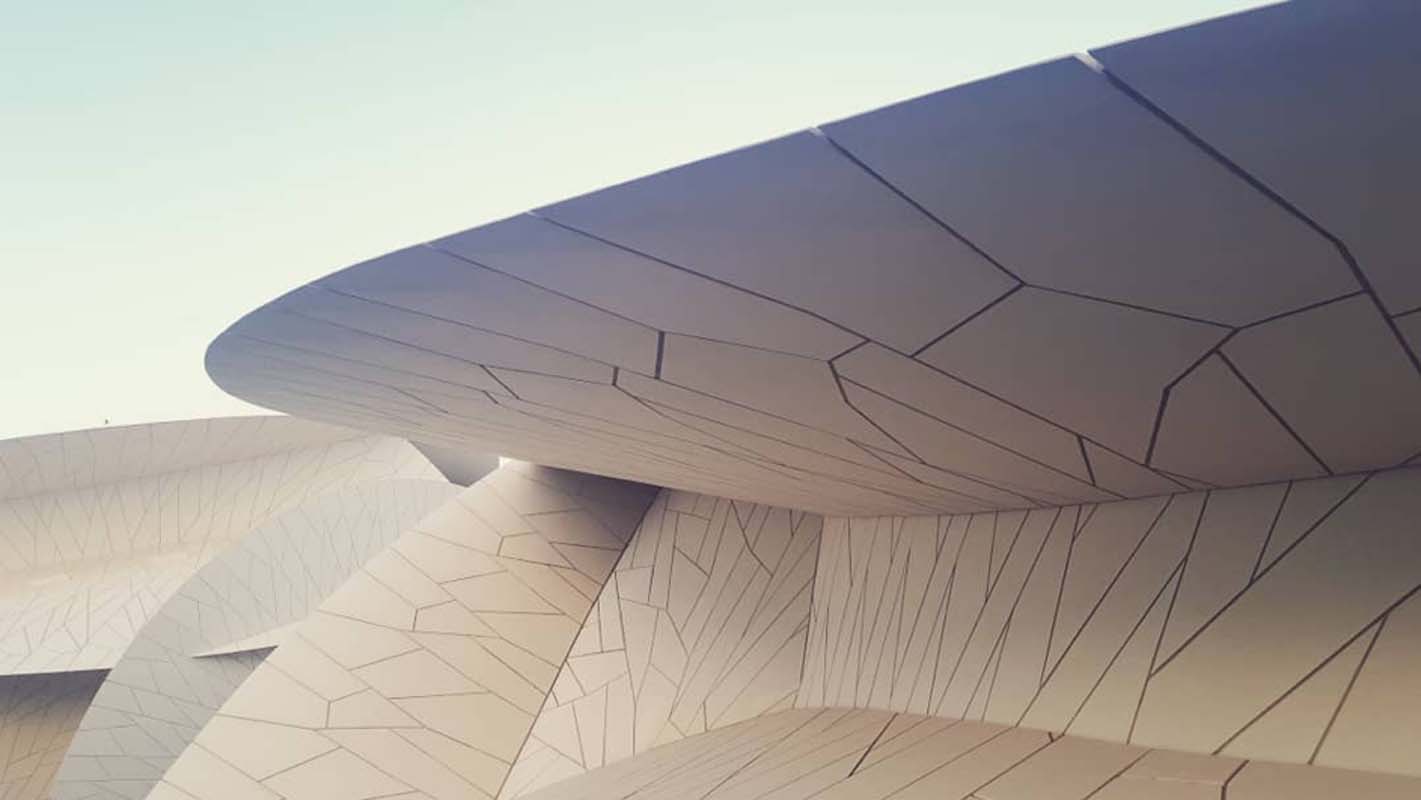

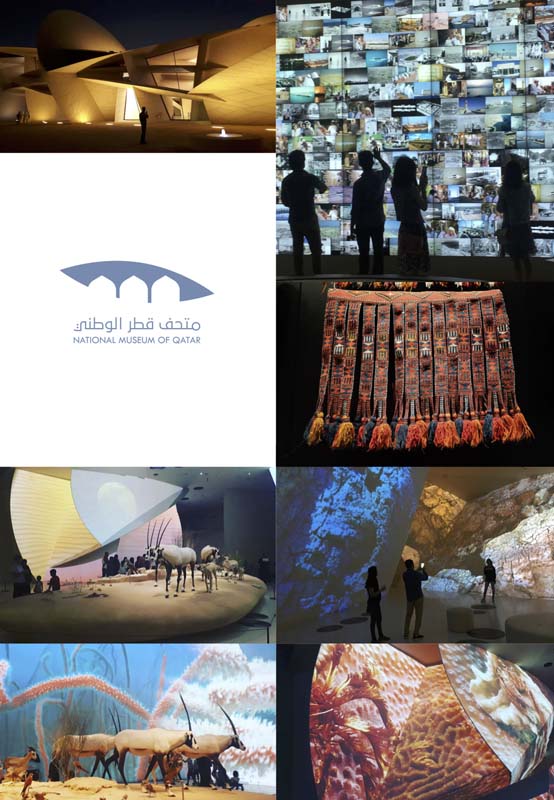

The Louvre Abu Dhabi and The National Museum of Qatar appear to the traveller as mirages in the desert, oases of art and artefacts emerging from a dusty oblivion. The latter, indeed, was inspired by the local ‘desert rose’ (the colloquial name for mineral crystalline clusters of gypsum or baryte found in arid sandy climates around the world).

In interviews, Jean Nouvel is a compelling interlocutor: self-assured, but witty; pensive, yet light-hearted. “I like to play with architecture,” he says, “it’s my favourite game”. He also likes the fact that his buildings are more famous than him, though that is perhaps changing. In 2008 he was awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize, which some have seen as a Nobel equivalent, and which is the highest honour a living architect can be bestowed. Previous winners have included Ieoh Ming Pei (’83), Frank Gehry (’89), Renzo Piano (’98), Norman Foster (’99) and Zaha Hadid (’04). This was preceded by the Wolf Prize in Arts three years earlier (of which Chagall and Tàpies were the first recipients), and the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in the late ’80s. In architecture circles at least, he is a household name, and his recent projects in Doha and Abu Dhabi have further bolstered his international reputation. It is, I think, a just recognition: his imagination, though daring and variegated, is less a prisoner to fantastical follies than, say, that of Ludwig II of Bavaria, who dreamed up extravagant castles with a seemingly more pathological frenzy (compare Visconti’s Ludwig). Nouvel’s method, instead, is to hold everything in until it begs to be let out, so that he can be sure his ideas are not only pleasing phantasms but also physically viable structures.

“Framing is the first thing. Framing is the basis of cinema. It’s the basis of photography and very often in architecture, we frame things.”

In his youth, he had wanted to be an artist, as young men do. But his parents disagreed, as parents do, urging him to be a scientist instead. Architecture was the eventual compromise. It has, evidently, turned out rather well, and his buildings have oft been praised for their ability to combine the big and bold with the intricate. He is a stickler for detail, and very much a proponent of ‘situational’ architecture, placing buildings in context, that is, in careful relation to their surroundings. He is strongly opposed to buildings ‘without roots’, cloned and ‘parachuted’ in with little regard for local aesthetics and sensibilities. For 100 Eleventh Ave., a residential tower in New York, he supervised the placement of every single window so that they should most pleasingly frame the cityscape; likewise, he opened up a side of the Institut du Monde Arabe by 3°so as to be able to ‘catch’ the (recently scorched) spire of Notre Dame. A building in Paris is unlikely to be right for Doha, he suggests, and vice versa. Nouvel’s structures, indeed, are striking for their variety - of style, placement and function. Before the two museums pictured here, he did everything from apartment blocks (eg. Nemausis 1 in Nîmes, ’87; Tower 25 in Nicosia, ’11; Le Nouvel in Kuala Lumpur, ’16) to gherkins (Torre Agbar/Glòries in Barcelona, ’05; Burj Qatar/Doha, ’12) to expansions and temporary pavilions (eg. The Opéra Nouvel in Lyon, ’93; Reina Sofía exp. in Madrid, ’05; Serpentine Gallery, temp. ’10 in London). It is, however, his projects involving the Arab world that I find the most impressive and, indeed, the most beautiful.

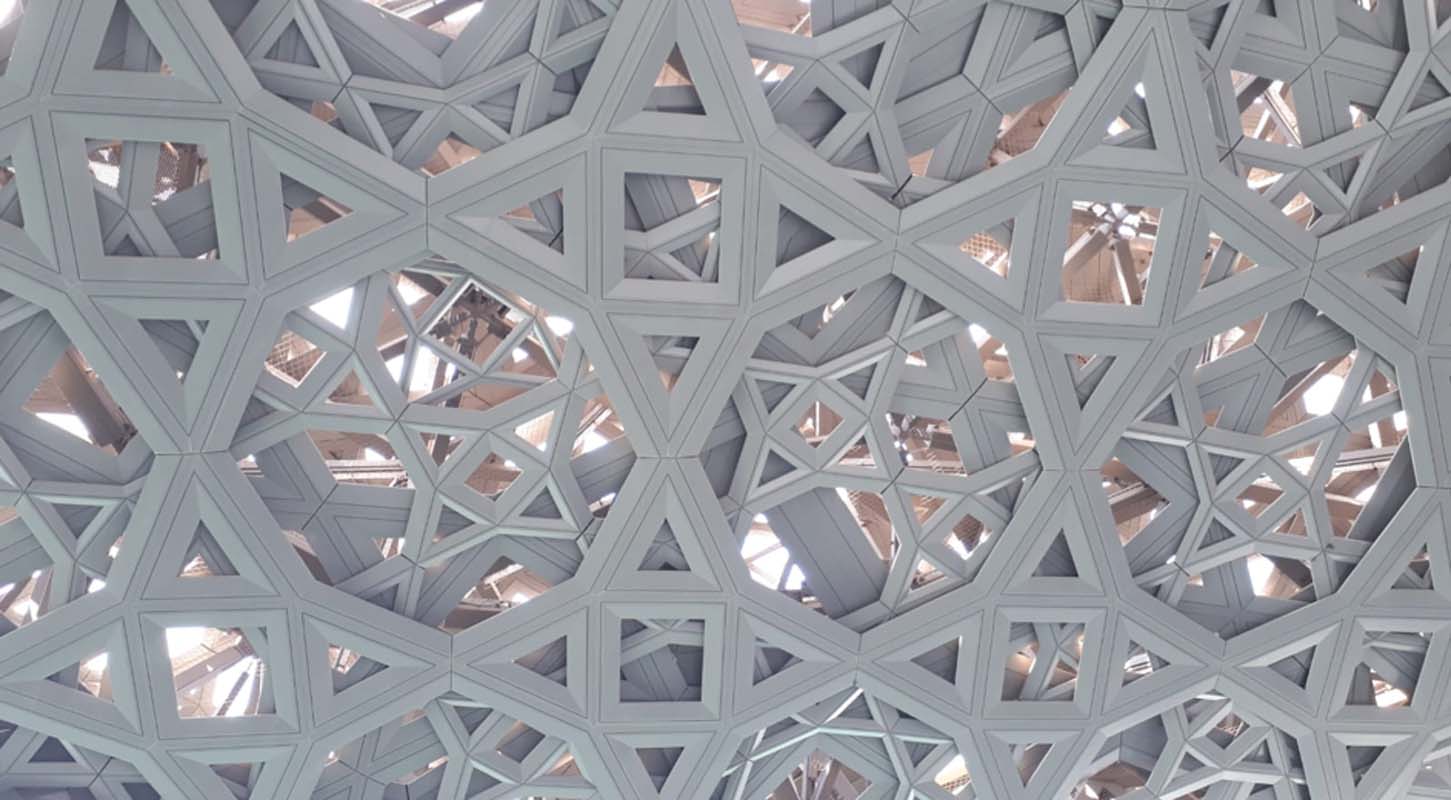

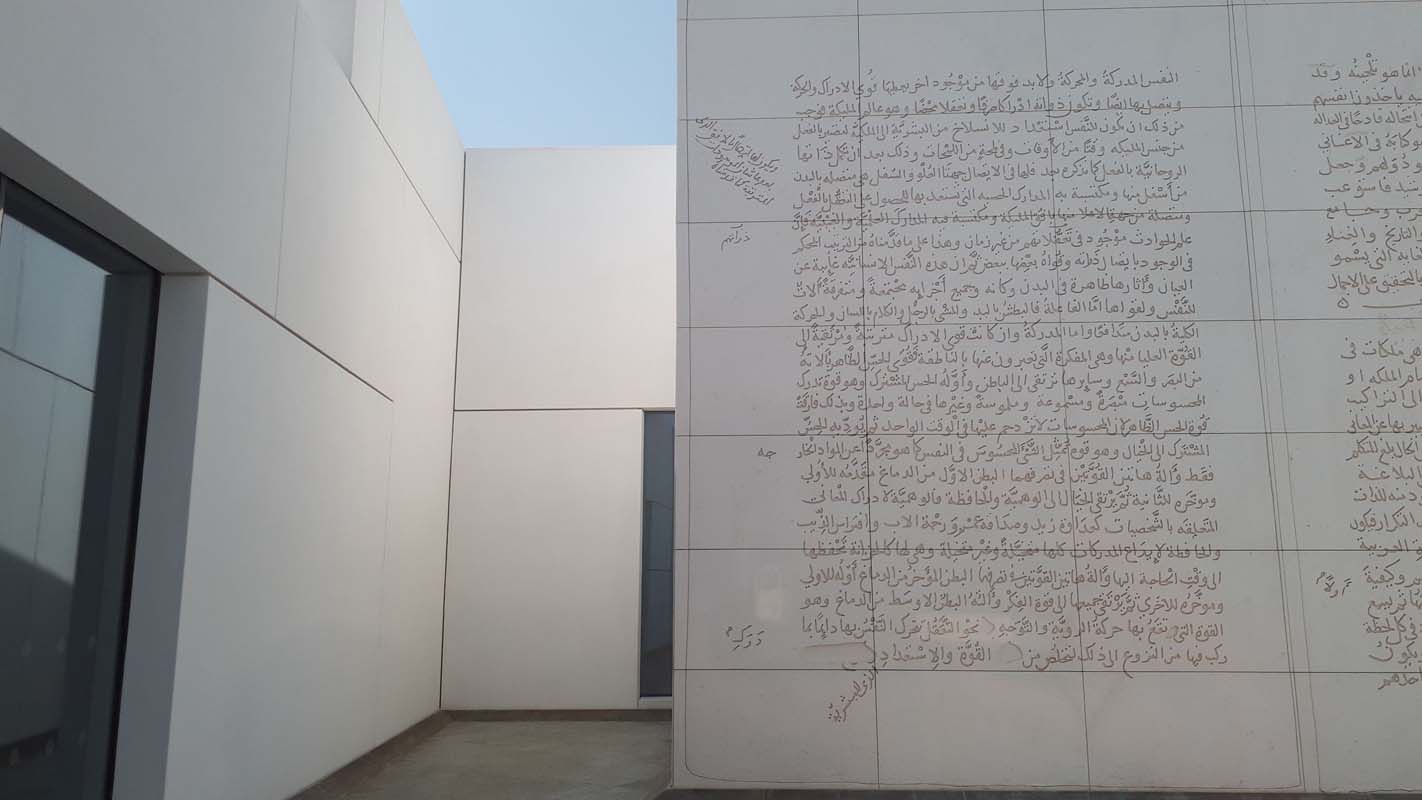

It all began with the aforementioned Arab World Institute (’87), conceived under the presidency of Giscard d’Estaing (’74-’81) and constructed during that of Mitterand (’81-’95) as part the latter’s Grand Projets series of urban developments. The most striking feature of the immense rectangular glass-clad façade are the metallic screens behind it: 240 photosensitive motor-controlled apertures that accommodate changes in light like the human eye, arranged in geometric motifs reminiscent of mashrabiya (latticework mainly on external windows; a common element of traditional Arabic architecture since the Middle Ages). A reinterpretation of this is again seen, on an even grander scale, as part of the ‘eternal white cupola’ that crowns the Louvre Abu Dhabi. A self-professed child of the structuralist generation (born in ’45, and thus a student during the protests of ’68), it is coherent that Nouvel should cite Baudrillard to justify his relationship with tradition: “Architecture is a mixture of nostalgia and extreme anticipation”. The former in fact printed these very words (in the original French), in red, across the minimalist doors he designed while converting, somewhat controversially, a church in Sarlat, Périgord (France) to a sheltered market. I am not alone in finding that approach a little heavy-handed and superfluous, but his spoken elaboration is cogent: if we seek merely to copy, quite formally, things of the past, the quality of such reproductions is bound to degenerate as methods change and processes are lost; we should therefore rather hold principles we nurture and deepen in order to invent anew.

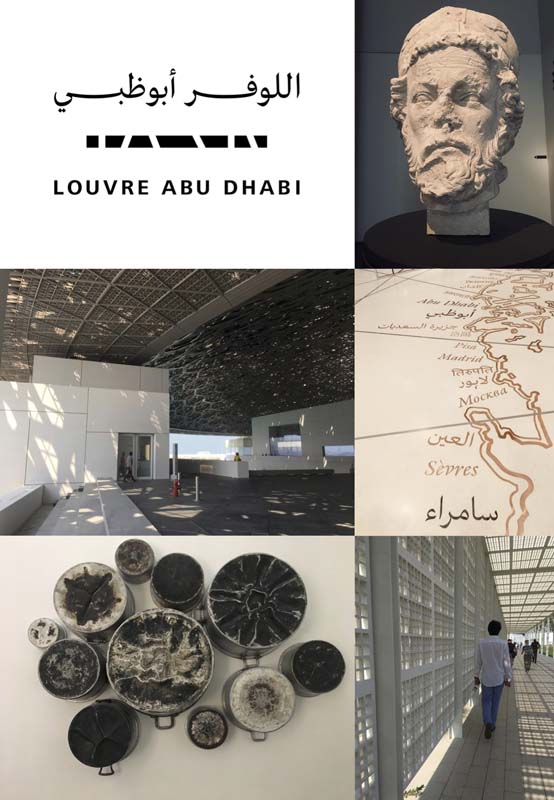

“Louvre Abu Dhabi,” the writers of the official guide proudly state, “was never going to be a simple adjunct to the Parisian original, a little Louvre in Abu Dhabi.” The aim was rather “to create a museum with its own unique identity”, something which Nouvel’s attentions have certainly facilitated. The whole area, and it is rather a large one (c. 24,000 sq. m./260,000 sq. ft., a third of which is gallery space) is its own microclimate: the dome and surrounding water provide a cooling effect, and the light breeze one feels under the cupola is a welcome relief from the searing desert heat. It is a peaceful place to be, and the pluies de lumières, showers of light that flicker and fade with the vicissitudes of the day, add a certain quasi-mystical dimension to the experience. It is the largest art museum in the peninsula, while the National Museum site, more historical in focus, is larger still (40,000 sq. m.).

One perhaps does not immediately associate the U.A.E. or Qatar with culture, but both museums are indubitably worth the quick detour. The Museum of Islamic Art by I. M. Pei, opposite the National Museum in Doha, is also one to visit, and has a restaurant by Ducasse.

Inside the Louvre Abu Dhabi: It may not have the same volume of works as the original Musée du Louvre, but then the latter can hardly be visited (exhaustively at least) in a day. It does, however, have unprecedented access to works from most of Paris’ major museums, having partnered with virtually all of them. The collection, by comparison, is relatively small, but can pack a punch. The strategy was rather to handpick one or two representative works from each era, movement, or civilisation, and organise a more or less chronological journey. Further, it boasts the rare privilege of housing an absolutely exquisite Leonardo, La belle ferronière (c. 1490-96), one of only twenty known works attributed to the artist. It was set to have two, with the acquisition of the Salvator Mundi (c. 1500), the most expensive painting ever sold at public auction, supposed to come in as the museum’s pièce de résistance. Bought from Dmitry Rybolovlev, the controversial Russian oligarch and current President of AS Monaco FC, for $450.3 m by Prince Badr bin Abdullah, Minister of Culture in Saudi Arabia (acting as an intermediary for MBS) at an auction by Christie’s in New York in 2017, it is equally notable as one of the key works embroiled in the Bouvier Affair, which exposed the extent of fraud in the art market. Its whereabouts are now – wait for it – unknown!

Inside the National Museum of Qatar: Like the Louvre Abu Dhabi, the layout is very clean, and very modern. Expertly curated, even though there would appear to be little to curate, with Qatar’s History hardly known for filling up innumerable annals since the dawn of time. The upshot of this, however, is that one is left with a fairly satisfying picture of the story of a nation. The museum is divided into three main categories across eleven galleries, and 1.5 km: Beginnings, Life in Qatar, and The Modern History of Qatar. The first room is one of the most arresting, with exhibits on the natural history of the desert and the Persian Gulf; subsequent rooms contain artefacts from Bedouin peoples, artfully reconstructed films of the tribal wars and documents and imagery relating to the discovery of Oil and later developments. The main point of fascination, over and above even the excellent picture and sound quality of the moving images, are the screens themselves, curved and interlocking, extensions and foundations of the outer structure.

Practical Information: Louvre Abu Dhabi is less than 90 minutes away from Dubai International Airport (DXB) while the National Museum of Qatar is a mere 15 minutes away from Hamad (Doha) International Airport (DOH). There are several daily flights to and from Colombo on Emirates and Qatar Airways respectively. Prices are generally reasonable, and there are excellent hotel deals with free stopovers going back or forth from Europe. Rooms were 26 $ (c. 4600 LKR) each per booking at the InterContinental Doha City, a five-star hotel. Seeing that we were a family, the check-in staff suggested an apartment: three bedrooms, three bathrooms, a kitchen, living and dining room for no extra charge. We were, I should point out, but three guests. A very decent place for a very decent price, then, though the ground floor restaurant, Al Jalsa Garden Lounge, is rather worthless and exorbitantly expensive (avoid the food & drink if you have time for alternatives). On the 55th floor, however, is a Cuban Bar (La Vista 55) with frequent happy hours, great music, dancing, decent cocktails and stunning views of city at night.